Basic

Always code as if the person who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live. -- Martin Golding

Production code needs to be of high quality. Given how the world is becoming increasingly dependent on software, poor quality code is something no one can afford to tolerate.

Production CodeIntroduction

Programs should be written and polished until they acquire publication quality. --Niklaus Wirth

Among various dimensions of code quality, such as run-time efficiency, security, and robustness, one of the most important is understandability. This is because in any non-trivial software project, code needs to be read, understood, and modified by other developers later on. Even if you do not intend to pass the code to someone else, code quality is still important because you will become a 'stranger' to your own code someday.

The two code samples given below achieve the same functionality, but one is easier to read.

Bad | |

Good | |

Bad | | Good |

Avoid Long Methods

Be wary when a method is longer than the computer screen, and take corrective action when it goes beyond 30 LOC (lines of code). The bigger the haystack, the harder it is to find a needle.

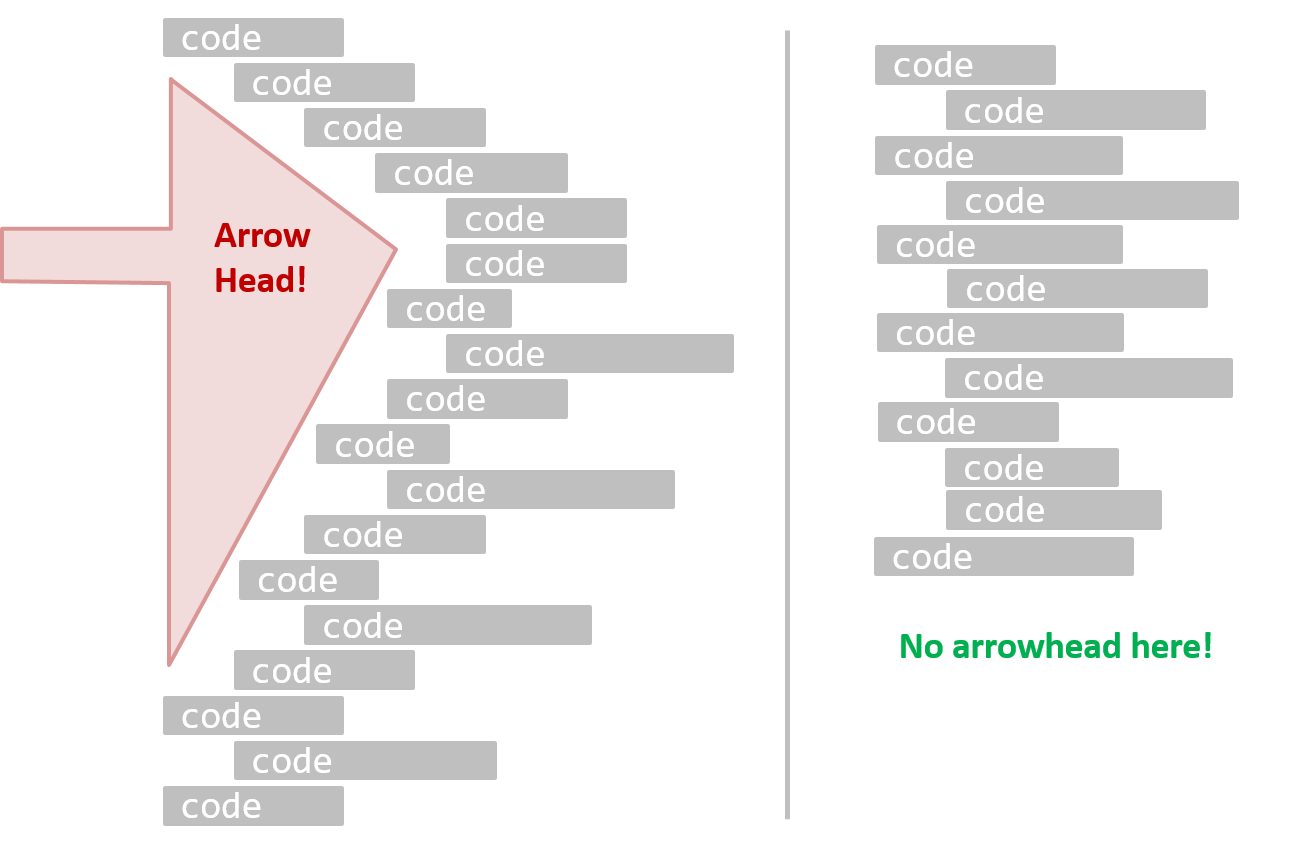

Avoid Deep Nesting

If you need more than 3 levels of indentation, you're screwed anyway, and should fix your program. --Linux 1.3.53 Coding Style

In particular, avoid arrowhead style code.

A real code example:

Bad | |

Good | |

Bad | | Good |

Avoid Complicated Expressions

Avoid complicated expressions, especially those having many negations and nested parentheses. If you must evaluate complicated expressions, have it done in steps (i.e. calculate some intermediate values first and use them to calculate the final value).

Example:

Bad

return ((length < MAX_LENGTH) || (previousSize != length))

&& (typeCode == URGENT);

Good

boolean isWithinSizeLimit = length < MAX_LENGTH;

boolean isSameSize = previousSize != length;

boolean isValidCode = isWithinSizeLimit || isSameSize;

boolean isUrgent = typeCode == URGENT;

return isValidCode && isUrgent;

Example:

Bad

return ((length < MAX_LENGTH) or (previous_size != length)) and (type_code == URGENT)

Good

is_within_size_limit = length < MAX_LENGTH

is_same_size = previous_size != length

is_valid_code = is_within_size_limit or is_same_size

is_urgent = type_code == URGENT

return is_valid_code and is_urgent

The competent programmer is fully aware of the strictly limited size of his own skull; therefore he approaches the programming task in full humility, and among other things he avoids clever tricks like the plague. -- Edsger Dijkstra

Avoid Magic Numbers

When the code has a number that does not explain the meaning of the number, it is called a "magic number" (as in "the number appears as if by magic"). Using a e.g., PInamed constant makes the code easier to understand because the name tells us more about the meaning of the number.

Example:

Bad | | Good |

Note: Python does not have a way to make a variable a constant. However, you can use a normal variable with an ALL_CAPS name to simulate a constant.

Bad | | Good |

Similarly, you can have ‘magic’ values of other data types.

Bad

return "Error 1432"; // A magic string!

return "Error 1432" # A magic string!

In general, try to avoid any magic literals.

Make the Code Obvious

Make the code as explicit as possible, even if the language syntax allows them to be implicit. Here are some examples:

- [

Java] Use explicit type conversion instead of implicit type conversion. - [

Java,Python] Use parentheses/braces to show groupings even when they can be skipped. - [

Java,Python] Use enumerations when a certain variable can take only a small number of finite values. For example, instead of declaring the variable 'state' as an integer and using values 0, 1, 2 to denote the states 'starting', 'enabled', and 'disabled' respectively, declare 'state' as typeSystemStateand define an enumerationSystemStatethat has values'STARTING','ENABLED', and'DISABLED'.

Structure Code Logically

Lay out the code so that it adheres to the logical structure. The code should read like a story. Just like how you use section breaks, chapters and paragraphs to organize a story, use classes, methods, indentation and line spacing in your code to group related segments of the code. For example, you can use blank lines to group related statements together.

Sometimes, the correctness of your code does not depend on the order in which you perform certain intermediary steps. Nevertheless, this order may affect the clarity of the story you are trying to tell. Choose the order that makes the story most readable.

Do Not 'Trip Up' Reader

Avoid things that would make the reader go ‘huh?’, such as,

- unused parameters in the method signature

- similar things that look different

- different things that look similar

- multiple statements in the same line

- data flow anomalies such as, pre-assigning values to variables and modifying it without any use of the pre-assigned value

Practice KISSing

As the old adage goes, "keep it simple, stupid” (KISS). Do not try to write ‘clever’ code. For example, do not dismiss the brute-force yet simple solution in favor of a complicated one because of some ‘supposed benefits’ such as 'better reusability' unless you have a strong justification.

Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it. -- Brian W. Kernighan

Programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute. -- Abelson and Sussman

Avoid Premature Optimizations

Optimizing code prematurely has several drawbacks:

- You may not know which parts are the real performance bottlenecks. This is especially the case when the code undergoes transformations (e.g. compiling, minifying, transpiling, etc.) before it becomes an executable. Ideally, you should use a profiler tool to identify the actual bottlenecks of the code first, and optimize only those parts.

- Optimizing can complicate the code, affecting correctness and understandability.

- Hand-optimized code can be harder for the compiler to optimize (the simpler the code, the easier it is for the compiler to optimize). In many cases, a compiler can do a better job of optimizing the runtime code if you don't get in the way by trying to hand-optimize the source code.

A popular saying in the industry is make it work, make it right, make it fast which means in most cases, getting the code to perform correctly should take priority over optimizing it. If the code doesn't work correctly, it has no value no matter how fast/efficient it is.

Premature optimization is the root of all evil in programming. -- Donald Knuth

Note that there are cases where optimizing takes priority over other things e.g. when writing code for resource-constrained environments. This guideline is simply a caution that you should optimize only when it is really needed.

SLAP Hard

Avoid varying the level of abstraction within a code fragment. Note: The book The Productive Programmer (by Neal Ford) calls this the Single Level of Abstraction Principle (SLAP) while the book Clean Code (by Robert C. Martin) calls this One Level of Abstraction per Function.

Example:

Bad (readData(); and salary = basic * rise + 1000; are at different levels of abstraction)

readData();

salary = basic * rise + 1000;

tax = (taxable ? salary * 0.07 : 0);

displayResult();

Good (all statements are at the same level of abstraction)

readData();

processData();

displayResult();

Make the Happy Path Prominent

The happy path (i.e. the execution path taken when everything goes well) should be clear and prominent in your code. Restructure the code to make the happy path unindented as much as possible. It is the ‘unusual’ cases that should be indented. Someone reading the code should not get distracted by alternative paths taken when error conditions happen. One technique that could help in this regard is the use of guard clauses.

Example:

Bad

if (!isUnusualCase) { //detecting an unusual condition

if (!isErrorCase) {

start(); //main path

process();

cleanup();

exit();

} else {

handleError();

}

} else {

handleUnusualCase(); //handling that unusual condition

}

In the code above,

- unusual condition detections are separated from their handling.

- the main path is nested deeply.

Good

if (isUnusualCase) { //Guard Clause

handleUnusualCase();

return;

}

if (isErrorCase) { //Guard Clause

handleError();

return;

}

start();

process();

cleanup();

exit();

In contrast, the above code

- deals with unusual conditions as soon as they are detected so that the reader doesn't have to remember them for long.

- keeps the main path un-indented.

Introduction

One essential way to improve code quality is to follow a consistent style. That is why software engineers follow a strict coding standard (aka style guide).

The aim of a coding standard is to make the entire code base look like it was written by one person. A coding standard is usually specific to a programming language and specifies guidelines such as the locations of opening and closing braces, indentation styles and naming styles (e.g. whether to use Hungarian style, Pascal casing, Camel casing, etc.). It is important that the whole team/company uses the same coding standard and that the standard is generally not inconsistent with typical industry practices. If a company's coding standard is very different from what is typically used in the industry, new recruits will take longer to get used to the company's coding style.

IDEs can help to enforce some parts of a coding standard e.g. indentation rules.

Use Nouns for Things and Verbs for Actions

Every system is built from a domain-specific language designed by the programmers to describe that system. Functions are the verbs of that language, and classes are the nouns.

-- Robert C. Martin, Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship

Use nouns for classes/variables and verbs for methods/functions.

Examples:

| Name for a | Bad | Good |

|---|---|---|

| Class | CheckLimit | LimitChecker |

| Method | result() | calculate() |

Distinguish clearly between single-valued and multi-valued variables.

Examples:

Good

Person student;

ArrayList<Person> students;

Good

name = 'Jim'

names = ['Jim', 'Alice']

Use Name to Explain

A name is not just for differentiation; it should explain the named entity to the reader accurately and at a sufficient level of detail.

Examples:

| Bad | Good |

|---|---|

processInput() (what 'process'?) | removeWhiteSpaceFromInput() |

flag | isValidInput |

temp |

If a name has multiple words, they should be in a sensible order.

Examples:

| Bad | Good |

|---|---|

bySizeOrder() | orderBySize() |

Imagine going to the doctor's and saying "My eye1 is swollen"! Don’t use numbers or case to distinguish names.

Examples:

| Bad | Bad | Good |

|---|---|---|

value1, value2 | value, Value | originalValue, finalValue |

Not Too Long, Not Too Short

While it is preferable not to have lengthy names, names that are 'too short' are even worse. If you must abbreviate or use acronyms, do it consistently. Explain their full meaning at an obvious location.

Avoid Misleading Names

Related things should be named similarly, while unrelated things should NOT.

Example: Consider these variables

colorBlack: hex value for color blackcolorWhite: hex value for color whitecolorBlue: number of times blue is usedhexForRed: hex value for color red

This is misleading because colorBlue is named similar to colorWhite and colorBlack but has a different purpose while hexForRed is named differently but has a very similar purpose to the first two variables. The following is better:

hexForBlackhexForWhitehexForRedblueColorCount

Avoid misleading or ambiguous names (e.g. those with multiple meanings), similar sounding names, hard-to-pronounce ones (e.g. avoid ambiguities like "is that a lowercase L, capital I or number 1?", or "is that number 0 or letter O?"), almost similar names.

Examples:

| Bad | Good | Reason |

|---|---|---|

phase0 | phaseZero | Is that zero or letter O? |

rwrLgtDirn | rowerLegitDirection | Hard to pronounce |

right left wrong | rightDirection leftDirection wrongResponse | right is for 'correct' or 'opposite of 'left'? |

redBooks readBooks | redColorBooks booksRead | red and read (past tense) sounds the same |

FiletMignon | egg | If the requirement is just a name of a food, egg is a much easier to type/say choice than FiletMignon |

Use the Default Branch

Always include a default branch in case statements.

Furthermore, use it for the intended default action and not just to execute the last option. If there is no default action, you can use the default branch to detect errors (i.e. if execution reached the default branch, raise a suitable error). This also applies to the final else of an if-else construct. That is, the final else should mean 'everything else', and not the final option. Do not use else when an if condition can be explicitly specified, unless there is absolutely no other possibility.

Bad

if (red) print "red";

else print "blue";

Good

if (red) print "red";

else if (blue) print "blue";

else error("incorrect input");

Don't Recycle Variables or Parameters

- Use one variable for one purpose. Do not reuse a variable for a different purpose other than its intended one, just because the data type is the same.

- Do not reuse formal parameters as local variables inside the method.

Bad

double computeRectangleArea(double length, double width) {

length = length * width;

return length;

}

def compute_rectangle_area(length, width):

length = length * width

return length

Good

double computeRectangleArea(double length, double width) {

double area;

area = length * width;

return area;

}

def compute_rectangle_area(length, width):

area = length * width

return area

}

Avoid Empty Catch Blocks

Never write an empty catch statement. At least give a comment to explain why the catch block is left empty.

Delete Dead Code

You might feel reluctant to delete code you have painstakingly written, even if you have no use for that code anymore ("I spent a lot of time writing that code; what if I need it again?"). Consider all code as baggage you have to carry; get rid of unused code the moment it becomes redundant. If you need that code again, simply recover it from the revision control tool you are using. Deleting code you wrote previously is a sign that you are improving.

Minimise Scope of Variables

Minimize global variables. Global variables may be the most convenient way to pass information around, but they do create implicit links between code segments that use the global variable. Avoid them as much as possible.

Define variables in the least possible scope. For example, if the variable is used only within the if block of the conditional statement, it should be declared inside that if block.

The most powerful technique for minimizing the scope of a local variable is to declare it where it is first used. -- Effective Java, by Joshua Bloch

Resources:

Minimise Code Duplication

Code duplication, especially when you copy-paste-modify code, often indicates a poor quality implementation. While it may not be possible to have zero duplication, always think twice before duplicating code; most often there is a better alternative.

This guideline is closely related to the DRY Principle .

Introduction

Good code is its own best documentation. As you’re about to add a comment, ask yourself, ‘How can I improve the code so that this comment isn’t needed?’ Improve the code and then document it to make it even clearer. -- Steve McConnell, Author of Clean Code

Some think commenting heavily increases the 'code quality'. That is not so. Avoid writing comments to explain bad code. Improve the code to make it self-explanatory.

Do Not Repeat the Obvious

If the code is self-explanatory, refrain from repeating the description in a comment just for the sake of 'good documentation'.

Bad

//increment x

x++;

//trim the input

trimInput();

Bad

# increment x

x = x + 1

# trim the input

trim_input()

Write to the Reader

Do not write comments as if they are private notes to yourself. Instead, write them well enough to be understood by another programmer. One type of comment that is almost always useful is the header comment that you write for a class or an operation to explain its purpose.

Examples:

Bad Reason: this comment will only make sense to the person who wrote it

// a quick trim function used to fix bug I detected overnight

void trimInput() {

....

}

Good

/** Trims the input of leading and trailing spaces */

void trimInput() {

....

}

Bad Reason: this comment will only make sense to the person who wrote it

def trim_input():

"""a quick trim function used to fix bug I detected overnight"""

...

Good

def trim_input():

"""Trim the input of leading and trailing spaces"""

...

Explain WHAT and WHY, not HOW

Comments should explain the what and why aspects of the code, rather than the how aspect.

What: The specification of what the code is supposed to do. The reader can compare such comments to the implementation to verify if the implementation is correct.

Example: This method is possibly buggy because the implementation does not seem to match the comment. In this case, the comment could help the reader to detect the bug.

/** Removes all spaces from the {@code input} */

void compact(String input) {

input.trim();

}

Why: The rationale for the current implementation.

Example: Without this comment, the reader will not know the reason for calling this method.

// Remove spaces to comply with IE23.5 formatting rules

compact(input);

How: The explanation for how the code works. This should already be apparent from the code, if the code is self-explanatory. Adding comments to explain the same thing is redundant.

Example:

Bad Reason: Comment explains how the code works.

// return true if both left end and right end are correct

// or the size has not incremented

return (left && right) || (input.size() == size);

Good Reason: Code refactored to be self-explanatory. Comment no longer needed.

boolean isSameSize = (input.size() == size);

return (isLeftEndCorrect && isRightEndCorrect) || isSameSize;